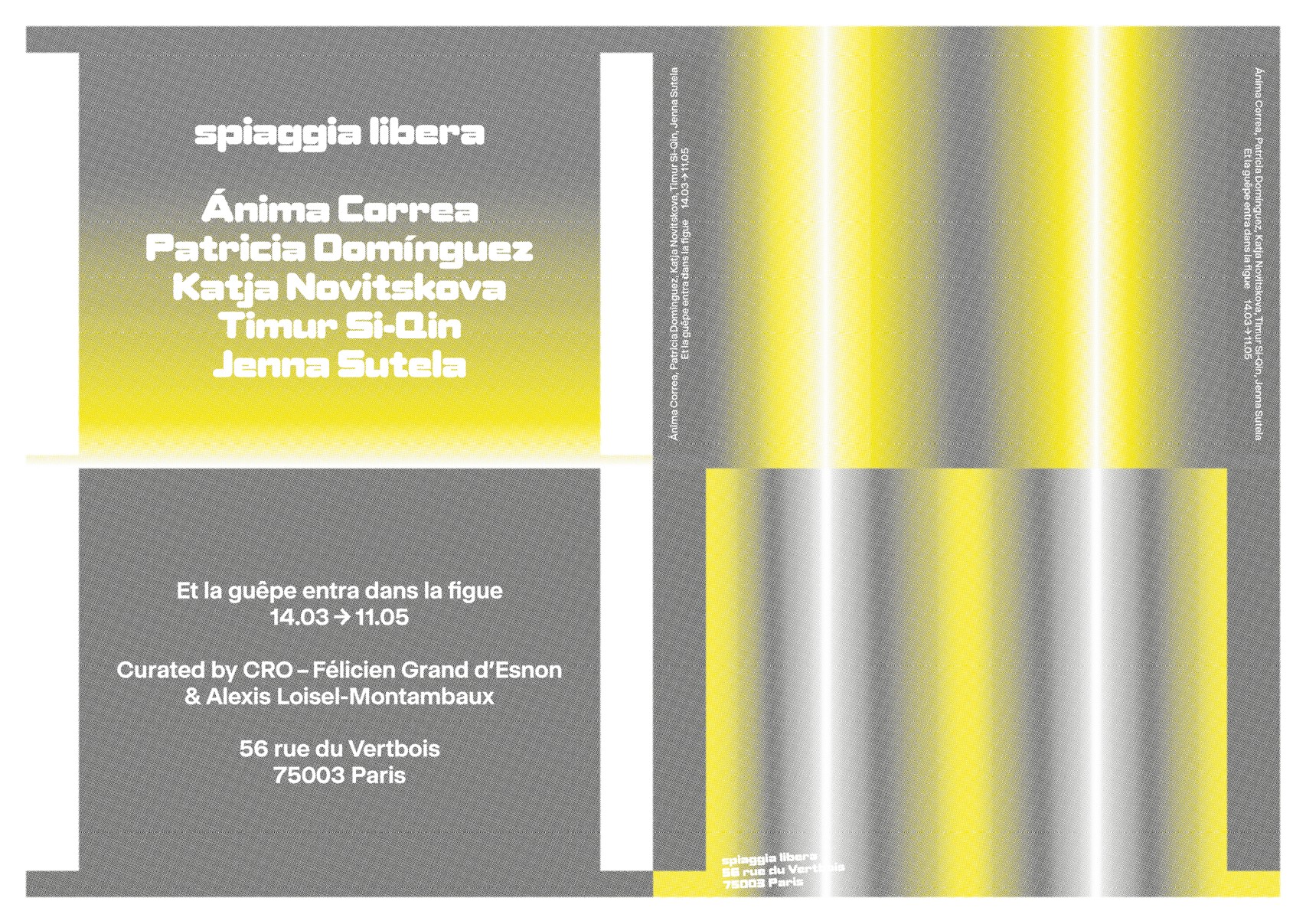

- Ánima Correa

- Patricia Domínguez

- Katja Novitskova

- Timur Si-Qin

- Jenna Sutela

And the wasp entered the fig

The forest lights up, the ocean gains ground, the earth rumbles and the wind blows ever stronger. It would seem that we have failed in our ritual, that the spirits of the living and the non-living feel scorned. The race for development has hastened us to turn our environment into a resource, to wither the gifts of past harmony and forget the ancestors who forged our history. Can we repair the ritual?

Et la guêpe entra dans la figue (And the wasp entered the fig) brings together artistic practices that explore alternatives to a linear vision of time and connect worlds that are often pitted against each other. They invoke ancestral technologies and hybridise technology and the living. Could it be that the capacity for adaptation, multiplication and hybridisation of species thousands of years old are technologies in themselves? In their search for non-human allies, some of them unicellular, invisibilised ancestral knowledge and augmented spiritualities, these artists are calling for a return to equilibrium, where humanity can learn again to live in symbiosis with its environment.

The title of the exhibition is inspired by the symbiotic relationship between the agaonid wasp and the fig tree, a mutualism born of thousands of years of co-evolution. The fig is its floral receptacle, which only it can penetrate. It is there that it is born, lays its eggs and decomposes. This interdependence also benefits the fig tree, whose pollen is dispersed.

— CRO

Félicien Grand d’Esnon & Alexis Loisel-Montambaux

Exhibition view, “And the wasp entered the fig”, Spiaggia Libera, Paris, 2024. © Aurélien Mole

The Earthware series by Katja Novitskova reveals infinite, non-linear visions of the evolution of our world. The wildebeest in Earthware 06.10.2017 faces us. Its glittering, almost digital gaze responds to the technology that has captured its image. Three visions are superimposed: the nyctalope automatic camera acts as an intermediary between the animal and human visions.(1) We find ourselves becoming spies for an immemorial technology as we observe this species that has adapted to survive and reproduce in a complex ecosystem; or perhaps it is the species that is observing us. This uncertain feeling is amplified in Earthware (Dreaming of Laurasiatheria), 2022, in which a hybrid mammal monitors us.(2) By mimicry - one machine reproducing another - algorithms have given shape to a new trans-species entity. The synthetic clay tablet on which the image is reproduced becomes the portal to a non-human vision, where the animal world reclaims its place as an ultimate technology. A technology once honoured on cave walls.

1 With a population of over 1.3 million, the wildebeest have the largest mammal population in Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park.

2 A type of biome characterised by the presence of a majority of trees whose leaves fall with the seasons.

Exhibition view, “And the wasp entered the fig”, Spiaggia Libera, Paris, 2024. © Aurélien Mole

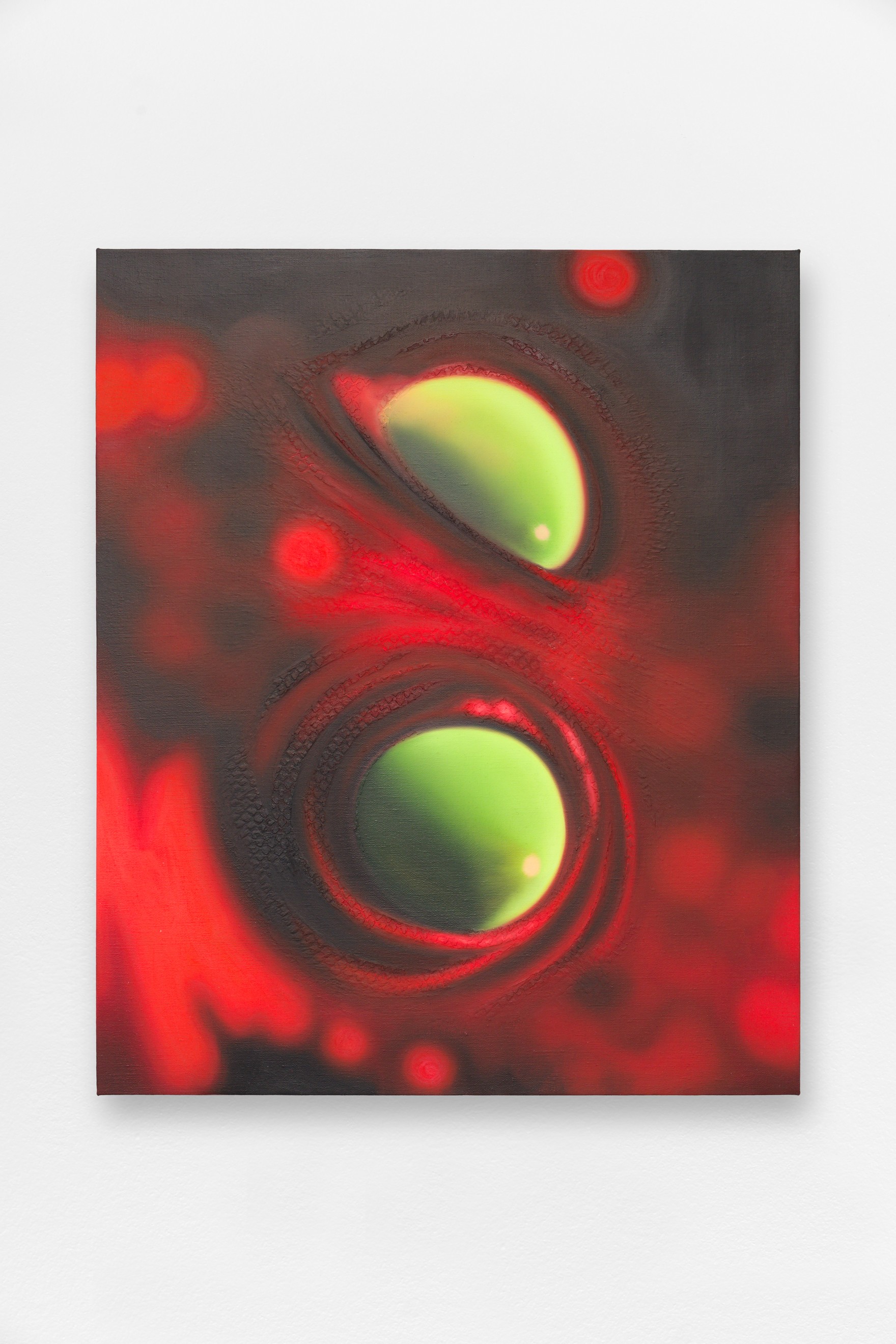

The marine bestiary that inhabits this suite of paintings by Ánima Correa guides us through the deafening maelstrom of images that blurs our perceptions. Like the shoal of fish in Bottomfeeder (piriwiri), we are drawn to the fluorescent green emanating from a fishing lantern, an irresistible, subconscious call to a technology that commands us. The living seem neutralised by this control technology, as if monitored by a menacing infrared vision. The cephalopod’s eye of Espejito XVII: Bellyache mirrors the seabed that humans have taken over, a world in which it tries to camouflage itself. The amorphous gaze of Sleeper’s barreleye fish, a being that can see into the abyss, reflects this broken link with the living world. The obsidian in Loose Lips Sink Ships becomes an object of divination for a mutated future.(1) The scrying of its surface, induced by LCD backlighting, reveals a hybrid and indecipherable face, at once Furby, kelp and stingray’s ventral mouth.

1 Obsidian is a glassy, reflective volcanic stone.

Exhibition view, “And the wasp entered the fig”, Spiaggia Libera, Paris, 2024. © Aurélien Mole

Ánima Correa, Sleeper, 2024, oil paint on linen, 61 x 51 cm. Courtesy the artist & Spiaggia Libera, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Ánima Correa, Bottomfeeder (Piriwiri), 2024, oil on linen, 61 x 51 cm. Courtesy the artist & Spiaggia Libera, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

In the shade of the rock, the flowers and flower buds turned skywards await pollinators. They probably will not come. These fragments of an ecosystem are captured in a 3D simulation created by Timur Si-Qin. The minerals and species represented in his Natural Origin series are from temperate deciduous forests in Upstate New York and Vermont.(1) The creative process, based on photographs and memories of explorations, is akin to a meditation, a devotion on the part of the artist to specimens that guarantee the balance of our environment and the survival of species. They form new icons born of a spirituality turned towards the environment: New Peace, a branded ecosystem designed by Timur Si-Qin. Here, technology and marketing are used as cognitive tools to recreate bridges between the living and the inorganic. Borrowing from the aesthetics of advertising, these images nevertheless reveal an underlying layer with organic forms, as if the internal flows of plants were becoming perceptible. These works form the radicles of a spirituality conceived as a technology that reconnects our collective emotions with the living and the inorganic. They bear witness to new techno-vernacular rituals inherited from animist practices.(2)

1 A type of biome characterised by the presence of a majority of trees whose leaves fall with the seasons.

2 CRO, “The Techno-Vernacular Wave. Shedding new light on the insights of vernacular practices in the era of new digital technologies”, Zérodeux, n°105 & 106, 2023.

Exhibition view, “And the wasp entered the fig”, Spiaggia Libera, Paris, 2024. © Aurélien Mole

Exhibition view, “And the wasp entered the fig”, Spiaggia Libera, Paris, 2024. © Aurélien Mole

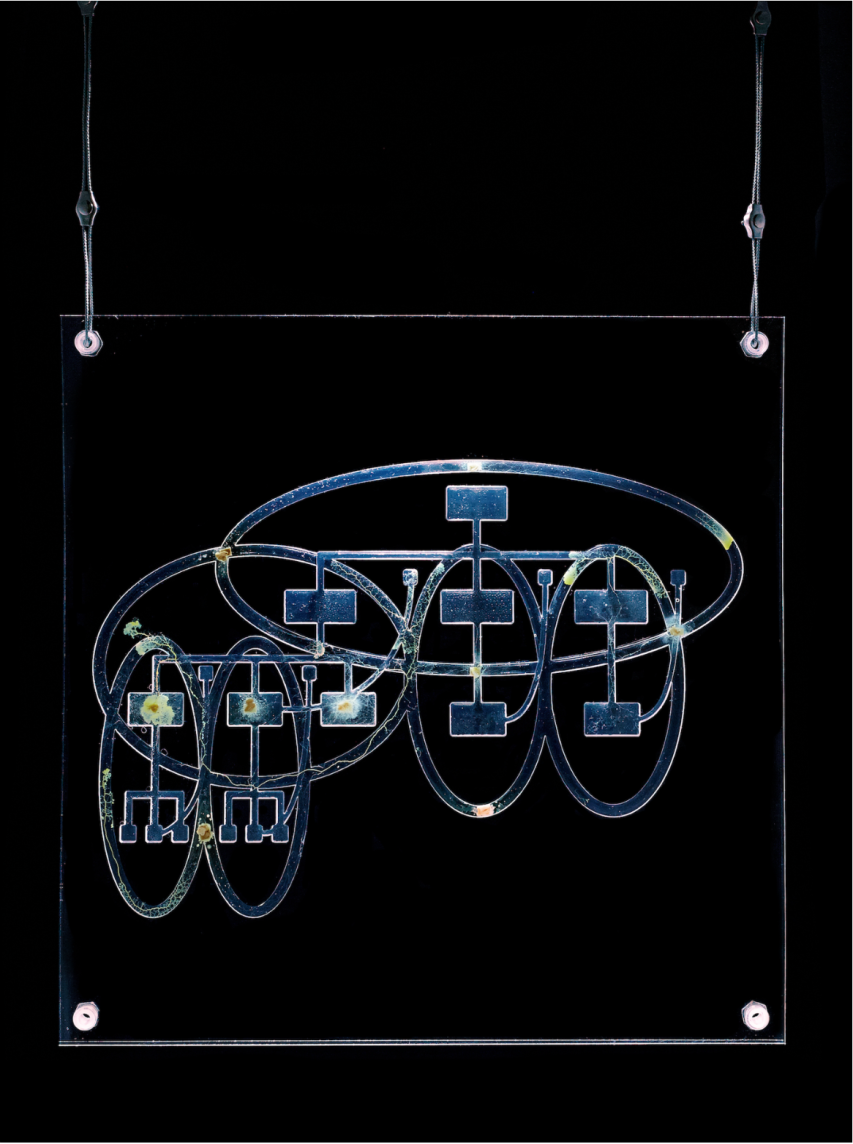

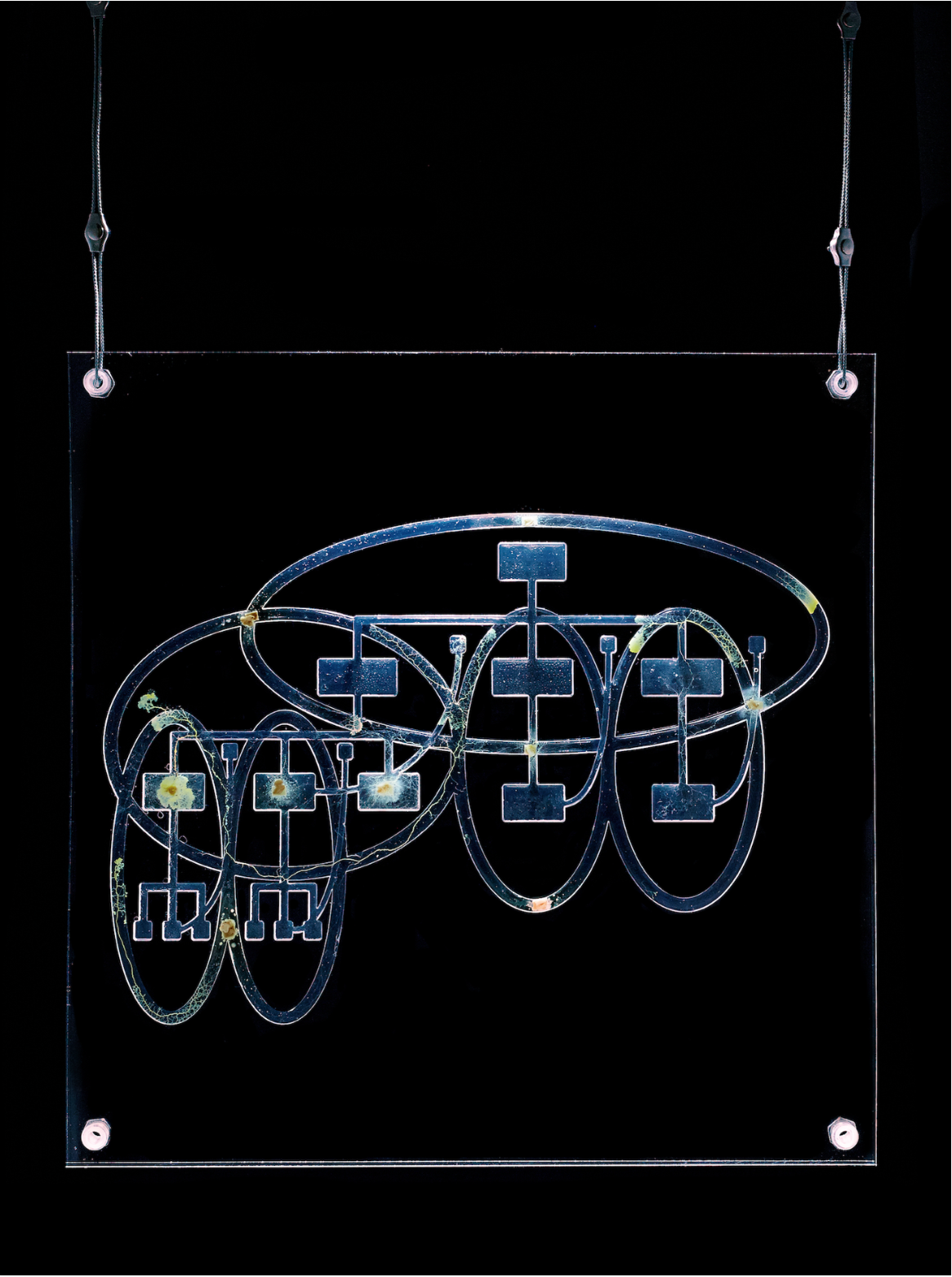

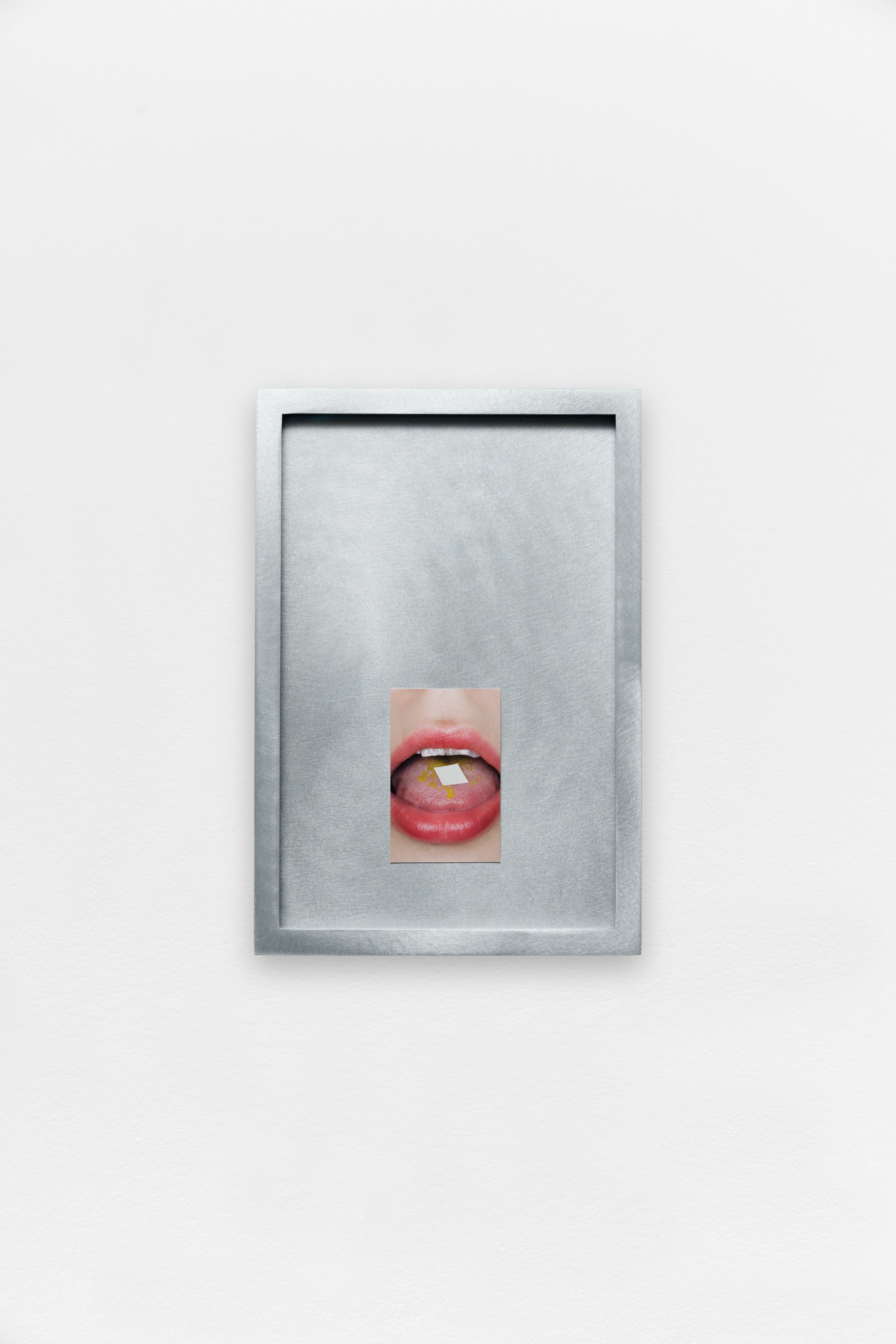

Jenna Sutela’s art establishes links with the more-than-human world. At the core of her work is a renunciation of anthropocentric hierarchies, towards decentralised forms of intelligence and organisation. The single-celled yet “many-headed” organism called slime mold, or Physarum polycephalum appears in some of Sutela’s seminal works. This ancient life form has inhabited the Earth’s dark and damp corners already way before our arrival. Today, the slime mold is known as a natural computer, appearing in different wayfinding experiments. Even if it does not have a brain or a nervous system as we know them, the slime mold is able to find the quickest route to its food source through swarm based spatial intelligence. From Hierarchy to Holarchy places rigid and centralised management systems in the human world against the environmentally adaptive, decentralised life of the slime mold. In Many-Headed Reading, Sutela entertains the idea of fusing together with the yellow blob. Ingesting the slime mold can be considered as an interspecies symbiosis, where the organism helps the artist to make connections where none previously existed, similarly to an artificial intelligence

Jenna Sutela, From Hierarchy to Holarchy, 2017, physarum polycephalum, agar and oats, CNC engraving on plexiglass, 40 x 40 x 1 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Jenna Sutela, Many-Headed Reading, 2016, print, aluminium frame, 22 x 15 cm. Courtesy the artist. © Aurélien Mole

Exhibition view, “And the wasp entered the fig”, Spiaggia Libera, Paris, 2024. © Aurélien Mole

An ethnobotanical vision of our relationship with the plant world is a vector of healing and harmony for Patricia Domínguez.(1) These interactions are sensory, therapeutic and shamanic. The character in her Matrix Vegetal video comes from a strange time. In this chlorophyll-fuelled tutorial, ayahuasca becomes the intermediary between humans and plants, between pre-colonial and post-colonial worlds, between ancestral knowledge and the rethinking of tomorrow’s world. Here, technological weaning and digital disconnection must precede a reconnection with plants. In this paraverbal communication, the leaves of the Mimosa pudica shrink under the fingers to the sound of a touch screen, and Datura flowers store data. For this new ritual, Patricia Domínguez drew inspiration from her apprenticeship with Amador Aniceto, a healer from the Madre de Dios region of Peru. An altar appears to celebrate a techno-vernacular spirituality and new alliances.

1 Ethnobotany is a science that looks at the relationship between human societies and the plant world.

Exhibition view, “And the wasp entered the fig”, Spiaggia Libera, Paris, 2024. © Aurélien Mole

Patricia Domínguez, Matrix Vegetal; comparto mi espíritu con tu flor, 2021, analogue photograph on paper, wooden frame, 100 x 66 x 3 cm. Courtesy the artist & The RYDER.

Patricia Domínguez, Esfinge Vegetal #2, 2023, brique de yoga, pvc et cheveux artificiels / yoga brick, pvc and artificial hair, 145 x 14 x 30 cm. Courtesy the artist & the RYDER. © Aurélien Mole

Patricia Domínguez, Matrix Vegetal, 2022, single-channel 4K video with sound, 21min14. Courtesy the artist & The RYDER.

About CRO

CRO is a curatorial duo founded in 2020 by Félicien Grand d’Esnon & Alexis Loisel-Montambaux. Through the hybridisation of technology and the living, they explore our mutant worlds, from a molecular level to our socio-cultural constructs. Their projects take the form of an interactive, multi-sensory ecosystem, calling on image, sound, texture and smell. Integrating the digital and physical living spaces, they disseminate their projects from the exhibition space to the teenage blogspot, from the paper of a magazine to the soundwaves of a podcast.

Among their recent projects: “The Techno-Vernacular Wave”, a two-part essay published in the magazine Zérodeux (2023); the group show “I cried at the end of a manga”, whose first chapter is currently on view at Ecole municipale des beaux-arts / Galerie Edouard Manet, Gennevilliers; and whose second chapter will open at the Château Centre d’Art Contemporain d’Aubenas (November 2024).

About Félicien Grand d’Esnon

About Alexis Loisel-Montambaux

Born in 1996, Paris.

Graduated from King’s College, London and the Courtauld Institute of Art.

Independent curator. After several experiences in France and abroad (Hayward Gallery, Collezione Peggy Guggenheim, Collection Lambert), he was exhibition and editorial projects assistant at the Fondation Carmignac (2022-2023), where he was involved in the preparation of exhibitions and catalogs - “Le Songe d’Ulysse” (2022) and “L’île intérieure” (2023) - as well as exhibitions for the Carmignac Photojournalism Award in Paris, at the United Nations headquarters in New York, and touring throughout Democratic Republic of Congo.

Born in 1995, Paris.

Graduated from Sorbonne, ESCP and Ca’ Foscari Venezia.

He works as part of the curatorial team at MO.CO. Montpellier Contemporain, where he assists the curators in the production of exhibitions and catalogs, including “Ana Mendieta. Search for Origin”, and “Huma Bhabha. A Fly Appeared and Disappeared” (2023).

He previously worked at the Fonds d’art contemporain - Paris Collections (2020-2023) on collection management, research and loans, and as a rapporteur to the acquisition committees.